Company Clocks

It seems to me that there are two clocks that control every product company. One marks events that disrupt the work that its people do, like a bell tolling. Another measures how long it takes to get something done, like a stopwatch ticking.

The Bell

The Bell clock marks off moments in time when the company or a team changes in some way the disrupts things. This might include:

- A team loses or gains members

- A project is canceled

- A priority shifts

- A competitor forces a position

- A planning cycle ends and a new one begins

- A piece of unmaintained code suddenly begins acting up

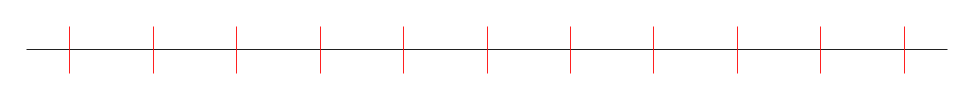

We can illustrate like this.

Time flows left to right and the red lines demarcate disruptions.

Time flows left to right and the red lines demarcate disruptions.

The Stopwatch

The Stopwatch clock measures duration: how long it takes to get something done. It might be governed by:

- Number of "stakeholders" that must be consulted

- Number of people on a team

- Amount of tech debt

- Amount of product debt

- Experience level of team

- Conceptual clarity of the project

- Compatibility of existing infrastructure with new needs

- Release process

- SLAs, contract with users

- The length of time it takes for a new team to become effective

- Primary communication media

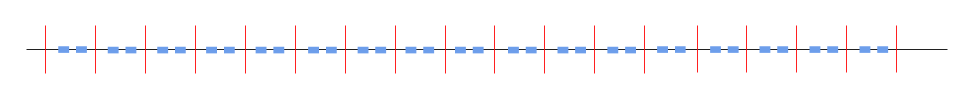

We can illustrate it like this:

The blue blocks demarcate pieces of work beginning, existing and ending. The end of one of these is when some value has been added.

The blue blocks demarcate pieces of work beginning, existing and ending. The end of one of these is when some value has been added.

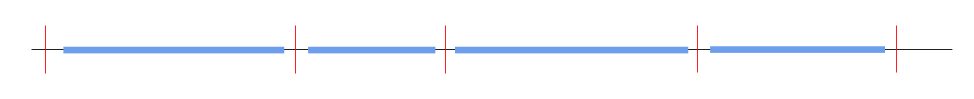

Things are never so regular as in both the above illustrations, some projects take longer and some teams have a harder time, and some changes affect certain departments or teams.

When companies are young and small these times are both typically short. In regards to bell time there are frequent shifts in priority as the team discovers what its users want and new ideas are experimented with. But stopwatch times are small too: a deploy is just a keystroke away, there's no one to consult or get clearance from, there are few users to annoy with new changes. There is little tech debt, which means creating tech debt is very easy.

When companies are mature and large these times are both typically long. Assuming the business is solid and well-run, it may be that no one tries to change anything for fear of rocking the boat. By this point, if a competitor attacks them, it hurts but not a lot and they'll live because they know their domain deeply and have reserves to weather challenges. On the other hand if they do want to change something there are levels upon levels of people to consult before launch. They have to carefully thread this change through a dozen legacy systems. And a change is more likely to disrupt millions of people relying on old behavior which means they need to give users time to adapt.

When companies are mature and large these times are both typically long. Assuming the business is solid and well-run, it may be that no one tries to change anything for fear of rocking the boat. By this point, if a competitor attacks them, it hurts but not a lot and they'll live because they know their domain deeply and have reserves to weather challenges. On the other hand if they do want to change something there are levels upon levels of people to consult before launch. They have to carefully thread this change through a dozen legacy systems. And a change is more likely to disrupt millions of people relying on old behavior which means they need to give users time to adapt.

Of course, few young and mature companies are without issue. But these are two modes I believe exist. And of course in some of these cases, abrubt changes and shifts still end projects. The point is that generally they give space for things to work.

Of course, few young and mature companies are without issue. But these are two modes I believe exist. And of course in some of these cases, abrubt changes and shifts still end projects. The point is that generally they give space for things to work.

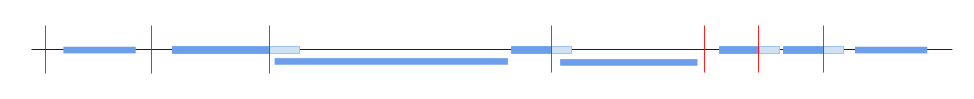

The in-between case is interesting and it's a place I think a lot of medium sized companies get into trouble. In this in-between case, changes happen nearly as much (maybe more) than they do at small companies but when they respond they have enough process and debt that it happens slowly.

Viewed in the graphic above, all the durations that fall on a bell ringing are canceled projects, wasted work—inefficiency. I put the next project on a different line to show that there is some time gained. But what isn’t shown is that typically there was a string of other planned work—work that was going to follow the canceled project—that also vanishes.

Viewed in the graphic above, all the durations that fall on a bell ringing are canceled projects, wasted work—inefficiency. I put the next project on a different line to show that there is some time gained. But what isn’t shown is that typically there was a string of other planned work—work that was going to follow the canceled project—that also vanishes.

In pathological cases it can feel impossible to get anything done—by the time one gets a project underway, things have changed under you. And because the company isn’t executing it fails to meet its goals and decides to change again.

To recover from a position like this a company has to either lengthen the time between changes, or shorten the amount of time it takes to get things done.

A company will always almost always try to shorten the time it takes to get things done for two reasons:

- Upper management has an outsized effect on bell time and refuses to relinquish it. In fact, they remain one of the only direct tools upper management has to influence things. They will always want the option to reorganize everything at any whim. And for the most part, that’s a good thing. (As long as it’s used well).

- Bell time is influenced by external pressures, namely competition and the market, so it’s harder to control in general.

There is a corollary to the first point above—upper management can dictate that stopwatch time change and push the responsibility down to the lowest parts of the company. In the worst cases management will simply demand that this time shrink with no further concessions. In the very worst cases they will do this but also force an artificial set of processes on top of it.

In the best cases, they will attempt to look at the variables that control these times and make hard decisions in order to be able to manipulate them. These are the companies that have a chance of succeeding beyond this point.

I think that most people who have worked at companies struggling with this will find the above familiar, maybe even obvious. But I also think sometimes obvious things are under-scrutinized because they are obvious. Every growing company should be thinking about these two clocks.

2018-08-28